How our Executive Director, Kelly Potvin became a prison abolitionist.

I am a prison abolitionist. I am also a survivor/victim of violence. These two positions may seem unorthodox within one person, but it’s exactly my experiences as a victim that led me to believe in the idea of prison abolition. I spend much of my professional life explaining prison abolition, but not a lot of time talking about my personal experience as a survivor. Victims’ rights and prison abolition actually go hand-in-hand if our goal is to create a truly just society. We just haven’t bothered to think of how we could accomplish both goals by working together.

As a prison abolitionist, I’m constantly addressing questions such as, “what should be done with ‘really bad people’” or “what about the victims?”.

I’m not sure how many “really bad people” we have in our society, but it feels like we are producing more and more of them by moving away from a just society and towards an increasingly police state. During the COVID-19 pandemic there have been so many challenges to the idea of basic income, police brutality, and systemic racism – basically all of our colonial structures, including prisons. More and more people can see that there aren’t so many “bad people”, so much as people whose lives have been full of challenges, riddled with poverty, perhaps addictions or mental health issues, all of which have led them to making bad choices. It’s not hard for me to imagine how many less incarcerated people there would be in this country if we implemented a universal basic income, de-criminalized street drugs, and stopped over-policing Indigenous and Black Communities.

The question that is often more difficult for prison abolitionists to answer is, “what about the victims of violent crimes and their families? If not prison, what justice do we offer them?”. This question is asked as though a prison conviction will change anything for a survivor or their family. That somehow sentencing someone to prison is imperative or even necessary for victims’ healing.

As many survivors know, rage is an important part of healing, which is why putting someone in prison feels like a good concrete way to soothe the rage. On the surface the formula is simple: I am hurt and now you will hurt. The prison system is a violent solution to a violent problem. I believe we can and need to do better. As a survivor I know this because I lived this experience. I was sexually abused by a family friend from the ages of 9 through 12. He was a well-respected man in our community who held an executive position in a large multi-national company. All those years I felt hurt and I felt rage, but it wasn’t until I was in my 20’s that I felt compelled to address what had happened to me as a child. During this time in my life I was working my first real job in the violence against women sector. Women would disclose their stories of sexual and physical abuse, and my job was to support them. Day after day I listened to these stories, so much like my own, and I felt like a fraud.

I was ready to do the work of confronting my experiences and turned to therapy, which was critical in motivating me to seek justice for myself and for what was taken away from me. At 30 years old I went to the police and reported the crimes. Just like the women I had worked with years ago, I sat and told my story. I relived, in great detail, every horror of the three years of abuse I endured as a child. I recounted the events several times with police until they were convinced I was credible. My disclosure initiated the complicated and problematic systems of policing, justice, and incarceration for my abuser.

But I had won. I had sought justice and received it. Now I would be healed – except I wasn’t.

After he was arrested, extradited and returned to Ontario, I then had to appear in court for a preliminary hearing and subsequent trial. Did the trial give me a sense of healing and closure? No, because a trial is only about winning and losing, and certainly not justice. The process of the justice system fueled my rage as a way to take my power back, and I continued because I believed it was important to win. To win would mean to be believed; to be validated by the system. I was under the belief that this would somehow help in my healing. If he was hurt, then my hurt would somehow be negated. Surely, all this re-traumatization had to be for something.

Before day two of the trial, the accused plead guilty in exchange for a sentence of two years less a day, which meant he would serve a six-month sentence in a provincial jail and then be released on probation. His crimes would be on record; I would be believed. I could heal. At the end of the process I was handed a letter from my perpetrator. In it, he accepted responsibility for what he had done and had explained that he too had been a child victim and he was only now learning about boundaries. He asked for my forgiveness. At the time I was so fueled by rage that I refused the letter and his apology. No letter was ever going to replace a childhood free from the violation of abuse.

I returned home after this process feeling a short-lived high. I commended myself for my bravery, between the judgement and therapy I should be all fixed up now. Wrong. As the weeks passed, I realized what I have finally come to terms with some 25 years later: my healing was never connected to my perpetrator’s punishment. It felt like it needed to be at the time, but there is no going back to a time before. Even if I was believed, it had still happened, I still had to relive it, I still had to decide who I was going to be after it was all over. In my healing journey, the years after the trial were some of the most challenging. I had done everything a survivor could do and still I was not “fixed”. I had an expectation that I needed to leave this behind me and move on, which was a notion reinforced by all of those who loved me. Unfortunately, I got stuck in that broken place for longer than I’d like to admit, and masked myself to my family and friends that all was fine. “Look at how strong I am” was my mantra. It wasn’t until after the birth of my daughter that I was able to start pulling my mask aside and show how my healing was very much still in process.

I write this not only as a survivor, but as a survivor with certain privileges.

I had resources and family and friends who supported me, and a child that I wished to be emotionally present for. I often think of those who do not have these same resources and support. As some of you might be aware, most police services across the country offer “victim services”. This is usually access to a social worker who can offer you 6 – 12 sessions to help you deal with your grief. This social worker’s office is typically located in a police building surrounded by police. If you are Black, Indigenous, or a person of colour, this will not be a safe space for you. But even if you are white, if you’ve been a victim of sexual assault, if you’ve lost a loved one, how could this service possibly make a difference in your healing? It is what we in women’s services (because women are disproportionately victims) know as wholly inadequate. These sessions cannot do more than scratch the surface of the healing that will take a lifetime.

Twenty-five years later I have more sympathy for his apology. Twenty-five years later, this thing that happened to me, that has happened to so many children and young women, has become a smaller part of who I am. In my experience, trauma can do one of two things: it can consume us, or if we can manage to accept it as now a part of us, maybe put it in a little box that we can control and let out to look at and measure how much we’ve healed. Nothing can change that it happened, not even a prison sentence. We have to find a way to incorporate the trauma into ourselves in a way that allows us to love ourselves and have healthy relationships again. Healing of this nature is a life-long process. Those of us without the resources to help us heal are often the people who end up in our prison system.

Perhaps my views on abolishing prisons were not completely formalized until I had an opportunity to visit a prison. Those visits have shattered every assumption I held that we have a better penal system in Canada than the US. That our system is based on reform and rehabilitation. Prisons are the least reforming place I have ever been to. The dynamics of power, control, and intimidation with policing people in prison is what catches you immediately. It’s in everything from the guards, the cameras, the metal detectors, even how the guards acknowledge each other but not the inmates. It occurred to me instantly upon my first visit that sending my perpetrator to prison caused a harm and did nothing to heal mine.

Prisons are not capable of reforming anyone, and yet over the past thirty years we’ve increased the number of incarcerated people in our country by 400%.

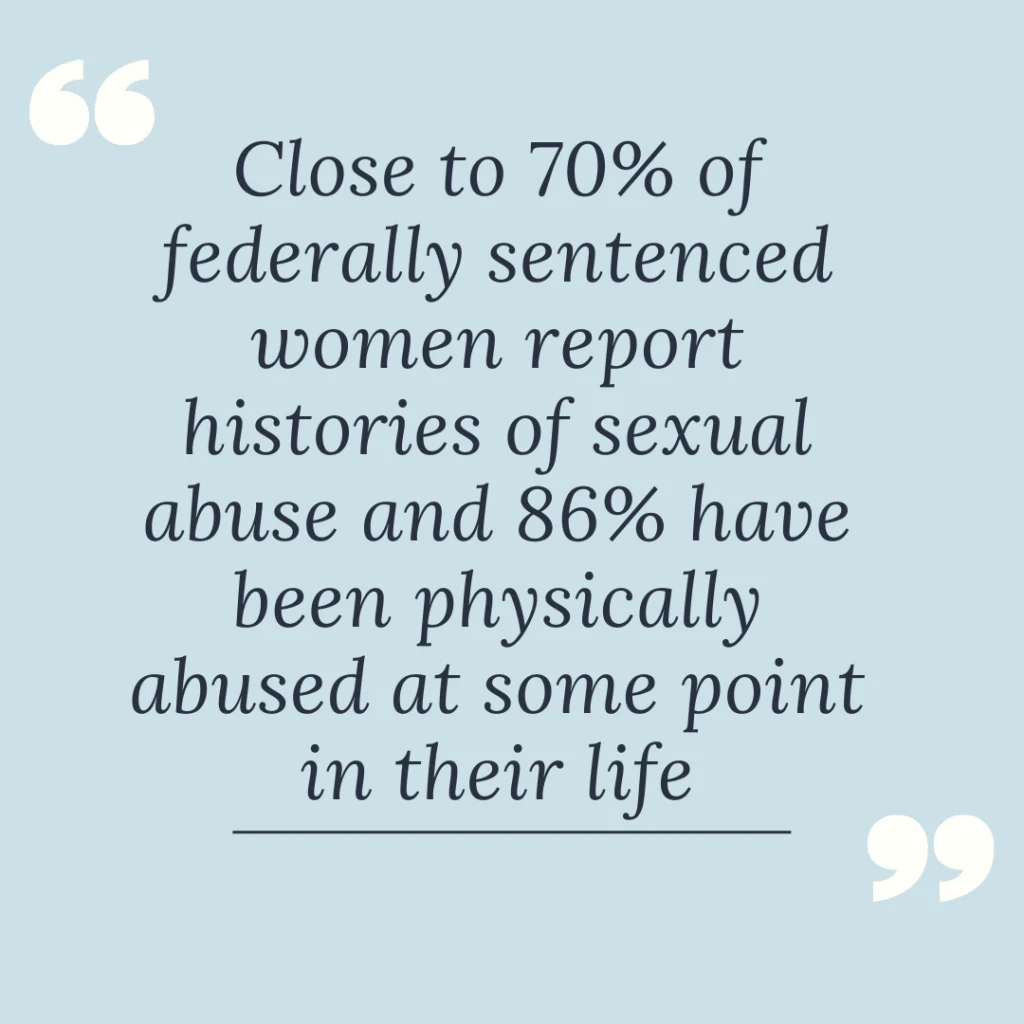

It’s estimated that at least 90% of incarcerated women are survivors of trauma. These women are subjected to strip searches, surveilled by male guards, and treated like children who are told when they can eat, go to sleep, or even make a phone call. These conditions do more harm in re-traumatizing women that when they are released, their trauma needs are unthinkable.

I was also surprised to learn that women are the fastest growing prison population worldwide, and it’s no different in Canada. Between the late 90’s when there was only one federal prison for women that held less than 100 women federally, to the new regional system that saw an increase to five federal prisons for women across the country. Today there are close to 500 federally sentenced women incarcerated in our country, the majority of them poor, women of colour or Indigenous, with mental health and addiction issues. But perhaps the most prevalent of all are issues of trauma. If you are a woman with any of the intersections of oppression, such as your race or if you are queer, not only will you not get adequate treatment inside for any underlying trauma, the carceral system of strip searching and control will continue to re-traumatize you repeatedly.

After meeting criminalized women and hearing their stories about how they came into conflict with the law, it became even more clear to me how broken our system is. Our incarcerated women are no different from me. Not substantively, and yet poor, racialized women who did not have the resources I had, and are sentenced to serving time which only compounds their trauma. In fact, for incarcerated women, being a victim of violence is deemed by our corrections system to increase the risk factors contributing to making someone a threat to public safety. The impact of treating trauma with more trauma is incomprehensible, and women’s survival of our penal system should only illustrate women’s resilience and not their danger to society.

Annual Report of the Office of the Correctional Investigator 2014-2015

The alternative to incarceration are practices of restorative and transformative justice. Processes which are based on principles of accountability and healing. But just as “de-funding” the police require a considerable investment in community programs, transformative justice programs require adequate services for both victims of crime and those who have committed the harm.

I am always surprised when speaking to people about prison abolition who still believe that we need prisons for really dangerous people. First of all, there are not as many dangerous people as one would think, and many of them have their own trauma story. Not that this excuses their crimes, but if we live in a society where we do not treat trauma, we will continue to produce our share of people so damaged that they have no regard for human life. I would further argue that if someone is truly dangerous, they would be better served by mental health professionals than prison guards.

The question still remains: how do we break this cycle that we seem to be trapped in? Society produces bad people, we lock them up in our cry for justice, they serve their time and become institutionalized, but whatever issues they went to prison with are only exasperated by experiences like strip searching, institutional rape, violence from guards, institutional racism – the list goes on. If someone finds a way to survive their time, they are often described by the system as “manipulative”. There seems to be no way for someone to be reformed upon their release.

Twenty-five years later, I am not interested in rage fueled, “lock him up” justice, but more in a transformative justice system that can focus on real healing for survivors, and finds a type of accountability for perpetrators that is also healing. If we want to break the cycle, if we want to keep our children safe, it means treatment for people who commit such offences because chances are, there is trauma at the root of it. By the same principle, we cannot end violence against women and girls unless we are prepared to do the work as communities to shift the imbalance of power, in all the intersections that exist. To do this work, we have to have uncomfortable conversations and provide adequate resources for everyone.

Click here to listen to a podcast about prison abolition ‘If we abolish prisons, what’s next?’

We are living a moment in history where the potential for change feels very possible, with Black Lives Matter, the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls report of genocide, Truth and Reconciliation, and calls to defund the police. These are all cries for a system of transformative justice that could change our country, that would close prisons, defund police, invest in communities, and provide healing for all. We live in a time when we are redefining justice in a way that must challenge all forms of oppression. As a survivor, this has given me the most dangerous emotion of all: hope. Hope of something better, for all of us.

Kelly Potvin is the Executive Director of Elizabeth Fry Toronto, Co-President for Thunder Woman Healing Lodge Society, and an Advocate for the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies who is living her best queer life with her family in Toronto.

Written by: Kelly Potvin

Elizabeth Fry Toronto ~ 416-924-3708 ~ Toll Free 1-855-924-3708 ~ info@efrytoronto.org